Confucius says…

There is a saying by the Chinese master- teacher Confucius which goes:

We all have two lives, and the second one begins when we realise we only have one

Luckily for all of us, the whole of Existence seem to conspire to help us come to that realization – all we have to do, is listen.

Hearing my own voice

Seven years ago, on a cold Friday night in July 2011, I was hit by a car. I remember the events of that night vividly, chronologically, and in great detail.

I remember the impact of my face and body slamming against wood and metal, and the sound it made when both my ankles broke. I remember my neighbor laying down on the pavement to hold my hand while we waited for the ambulance to arrive. I remember how angry I was with the paramedic when he cut into my jeans in order to reach and stabilize my feet (it was my only pair that fit!).

I remember registering pain in my abdomen, and having the realisation that this could be really serious; that I may have internal injuries, and that I may even die.

And then I remember, very clearly, a protestation coming up from somewhere inside myself, an urgent conversation between myself and the Fates as I lay there, a little bit broken, on the ground:

“…but I am not done yet.”

Just that.

No great unfulfilled bucket list. No big regret, no undeclared love, no unsaid words. Just a knowing.

I was not done yet.

I don’t speak of this part of that night often. I consider it one of a few holy moments in my life – those moments where something seemingly insignificant happens and then proceeds to disrupt the continuum of one’s life completely.

Nothing changes if nothing changes

It is no secret that the girl who stood up out of my wheelchair five months later was different to the girl who first sat down in it. I have often said that the accident was a great blessing, and that it had saved me from myself – but if I’m really being truthful, it was that Voice inside me, fighting for a second chance at a life, that changed me. It was in that moment when something new came alive within me.

This does not mean I took that second chance and made the most of life from that point forward. How I wish I could say that! It took me seven long years to circle back to the realization that I only have one life, and that now was time to make the most of it.

But first I had to learn to stand again, and then I had to learn to be around people again. Then I had to learn who I was, in a post-wheelchair world.

I lost all the weight I gained while I was in the wheelchair. I learned to walk from scratch with the help of some really special biokineticists at SSISA. I even ended up running a couple of half-marathons.

Then I repeated the pattern of self-abandonment I was so good at before the accident – I first neglected my fitness, and then abandoned it completely. Then I gained all the weight back again.

All the while life around me continued.

I focused on work instead of on myself, trying to navigate changes in the organization, my role, my deliverables, my team and my reporting lines. The more time passed, the more my life resembled what it was before the accident.

No Voice. No Hope.

On the outside things looked all bright and shiny, but on the inside I just kept spiraling. I felt anything but alive – I felt sick most of the time, I was constantly tired, I cried almost every day. Simply styling my hair became an impossible feat. I was exhausted by my attempts at a ‘normal’ life, and despondent because of them.

I continually searched for affirmation outside of myself, without ever really listening to what I needed or considering how best to nurture myself.

I often wished that I could just end.

Laos

In August 2016, I was given an opportunity to volunteer with GVI in Laos PDR, teaching English to novice Buddhist monks. It was my first trip outside of South Africa, traveling solo to a country where I did not read, speak or understand the language, and where my prized western corporate skill-set did not mean a thing.

It was there, in the picturesque UNESCO-protected town of Luang Prabang, where I heard that Voice again. That’s where I remembered how it feels to be excited and alive in every fiber of my being, what it feels like to really add value.

I walked up and down the village streets, in rain or shine, taking photos, absorbing everything about this strange and wonderful place, and feeling how entirely new spaces open up inside myself.

It was there, between the Nam Khan and Mekong rivers, within the temples and the alms-giving processions and chanting ceremonies, where I discovered who I was again, and I keenly realized that the things I do in the hope that other people will accept me, may not be the best thing for me after all.

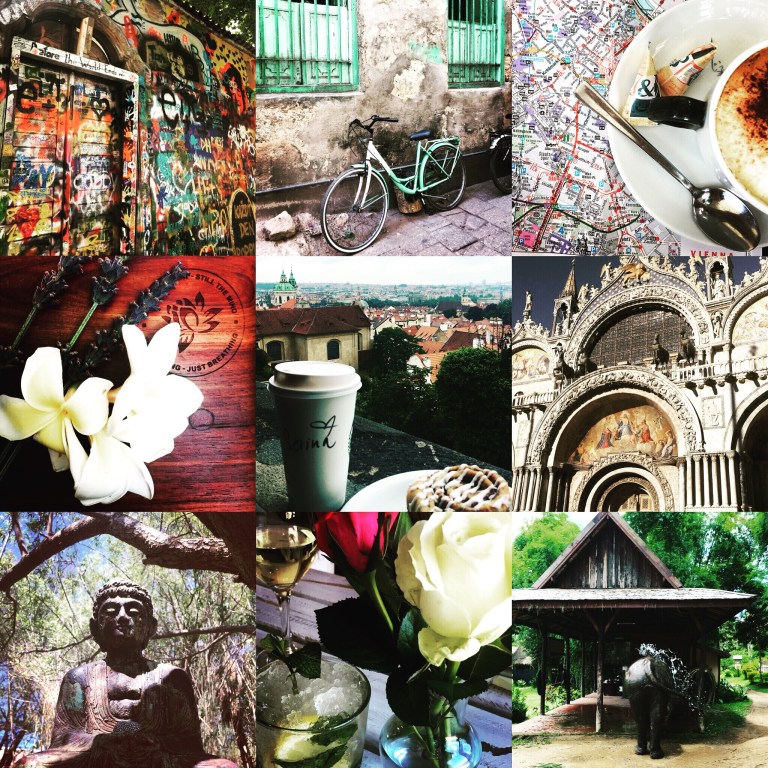

A period of frantic travel

When I returned from Laos, everyone remarked on how alive I seemed.

As the weeks went by, everyone remarked on the rapid loss of that aliveness.

I didn’t think anything of it at the time – I thought it completely normal that my ‘usual state’ was one of fatigue and diminished vitality. I fully subscribed to the idea of sacrificing my life force in order to make a living.

But once I have tasted that aliveness, I wanted more. I liked who I was over there. I was brave, and funny, curious and resourceful. I could not yet see that the ”over there” me and the ”over here” me were the same person.

For the next two years, I traveled frantically, escaping my everyday reality in an attempt to recapture my aliveness, trying to take it hostage and bring it back with me. It was like asking an endangered species to thrive in captivity – it dimmed quicker and quicker every time.

Endings and beginnings

Somewhere over the course of the last year things became clear: in order to really take care of myself, in order to stop this cycle of self-abandonment, I would need to move on.

I can say many things about the events which lead up to me leaving a career after 15 years of single-minded dedication. I can list the feelings and stages of grief I cycled through as I was making the toughest decision of my life to date. I can describe sleepless nights, and the sense of losing my place in the world.

But there was a certain inevitable peace about it, as if it was written in the stars: I only have this one life, and I feel compelled to make it a worthy one, one I can call my own and be proud of, one in which I can be myself and celebrate the woman I have become.

Camino de Santiago de Compostela

Once the decision was made, everything seemed to fall into place. I quit my job, booked my flights, bought a backpack, and left for Spain.

The Camino de Santiago is an ancient pilgrimage route, a collection of paths starting all over Europe, all leading to the tomb of the Apostle James in the Spanish city of Santiago de Compostela. Many people have asked why I chose to walk the Camino, and I still don’t have an eloquent answer to the question. I sometimes think it is the other way around – that I did not choose the Camino, but that the Camino chose me.

Be that as it may, it was one of the most profound journeys of my life.

My Camino started in Roncesvalles, in the foothills of the Pyrenees mountains in Northeast Spain, in Basque country, on a freezing cold and snowy Sunday in May.

From there I walked westward for 40 days and 40 nights, covering more than 800km across 6 provinces, to arrive at the magnificent cathedral in Santiago de Compostela, and see its famed boitafumeiro swing.

I walked through snow, rain, mist and bright sunshine, on slippery forest tracks and over steep and rocky mountain trails.

My pack was often heavy, my feet hurt most of the time, and at one point I had a blister inside of a blister. I contracted a severe chest infection, about five days into the journey. At times I ran a fever so high I could feel sweat pooling inside my ears.

With every step I could feel myself walking out from under my old life, my old self, away from who I was before. I realized that sometimes an emotional burden is heavier than a physical one and that a fever has to rage until all the bad stuff has been burnt away. Day by day I could feel myself healing – physically, mentally and emotionally – as I walked across the plains, breathing fresh air, drinking water from fountains and sharing simple meals with my fellow pilgrims.

I made friends with my shadow, and then I made peace with my reflection. By now I can greet myself with a smile, and know that I will never again disrespect myself so much that I will drown my own voice and attempt to replace it with that of another.

I have never felt more alive.

It was a profoundly transformative experience.

A new life

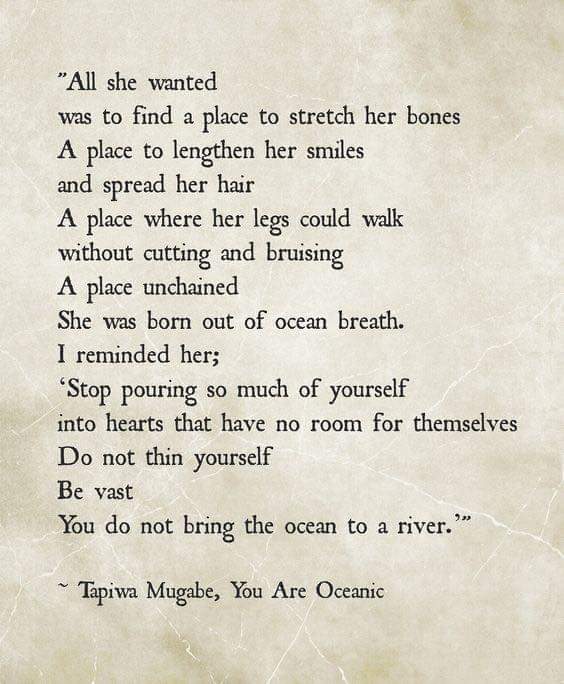

There is a poem called “You are Oceanic”, by Zimbabwean poet Tapiwa Mugabe, that I think encapsulates it best:

In the end, I think it is about giving oneself the space to just be who you are, and then be that in a large way, with abandon. To have one’s own permission to be vast.

To feel what it feels like to inhabit oneself fully, unbroken, with one’s life force intact.

It is to know one’s own resourcefulness and limits, and its about learning how to access one’s own power, and call it back once it has gone astray. And it is about learning kindness, mostly to oneself.

I owe myself the biggest apology for putting up with what I didn’t deserve.

I have been back home for some weeks now, and I’m spending my days whittling away at creating a new life. It is not as easy as I thought it would be. One cannot simply redistribute one’s weekend activities and call it a life. Creating is not a passive process.

I still have a lot of healing to do, and it is an active and ongoing practice. It requires of me to be present, and engaged in my own well-being. I’m required to evaluate my choices and to be vigilant to not fall back into old ways of thinking or familiar patterns of behavior. I have to choose myself every day.

But my heart is open, and I am at peace. I’m getting glimpses of who I can be next.

I am definitely not done yet.

Thank you Sorina for sharing your journey with me. It is an honour to read. I can see so many more chapters manifesting. I am very grateful that I have had the privilege of being with you on the Italian Via Francigena. Light and Love Suey x

LikeLiked by 1 person